According to the Ming Dynasty’s Tian Gong Kai Wu (The Exploitation of Natural Resources), the handmade ceramics cups from Jingdezhen require 72 processes from the beginning to the final product, not including the smaller intricate details.

The complexity of these 72 steps highlights the craftsmanship involved. Due to changes in materials and techniques in modern times, the process of making ceramics has evolved. However, the beauty of traditional 72-Step handmade ceramics cups, shaped by the 72 steps, remains irreplaceable.

The process of making porcelain in Jingdezhen begins with surveying the mountains. The aim is to find clay suitable for ceramics, which is mined from porcelain stone deposits. Experienced masters rely on their extensive knowledge to locate exposed mineral veins on the surface.

However, the exposed veins are very hard and difficult to mine. As a result, clever workers developed a method of firing the stone to make it easier to extract.

They would pile firewood on the exposed veins, set it ablaze, and then douse the fire with water. The thermal expansion and contraction would cause the stones to crack, allowing workers to dig along the fissures, forming a porcelain stone mine.

Today, these techniques have been streamlined using modern equipment.

Porcelain stone deposits are often found deep in the mountains. In the past, transporting the stones was done manually, using carrying poles and bamboo baskets to slowly move the stones to the water mills along the riverside.

There, the stones would be turned into a slurry suitable for making ceramics. At the water mill, the workers first break the stone into fist-sized pieces to make it easier for later crushing. Crushing, also known as “chong shi” (pounding stone), involves placing the porcelain stone into a mortar, where the pounding wheel, powered by the falling water, crushes the stones.

The crushed porcelain powder is then removed and poured into a washing pit, where it is washed with clay for several days, removing impurities. The water is then transferred to another pool to allow sedimentation. After draining the excess water, what remains is a concentrated porcelain slurry, which is ready for use in the next steps of production.

After the porcelain slurry has been clarified and washed, it is left to rest in a cool place for a few more days until it can form into lumps.

These lumps are then extracted by placing them into a rectangular mold, where excess clay is removed using a cutting line. The mold is then removed, and the result is a clay block similar to a brick. This is referred to as bai dun (白不) or dun zi (不子) in Jingdezhen, and it represents a rough processing stage in porcelain production.

The neighboring Qimen County in Anhui also produces porcelain-grade bai dun, with a pure color and fine quality. These are transported via the Shunchang River to Jingdezhen, where they are sold at stores specializing in white clay.

The porcelain clay is either traded for cash or on credit to porcelain workshops. This business model greatly contributed to the development of Jingdezhen’s porcelain industry.

The 72-Step handmade ceramics cups requires glazing, and glaze must be mixed with glaze ash. In Leping, the glaze ash is made by stacking a type of bluish-white stone with a plant called fengwei grass and firing them. Afterward, the mixture is placed in large jars and aged for three years with special ingredients before it can be used as glaze ash.

When preparing the glaze, it is mixed with bai dun, and water is added to adjust the consistency. The glaze is then prepared in different proportions depending on the type and size of the porcelain.

During the firing process, the porcelain blanks must be placed in firing boxes, each kept separate to ensure the cleanliness of the body and prevent damage.

The clay used to make these firing boxes does not need to be refined, and the boxes are lightly dried before being placed in a kiln for empty firing, a process called du xiang (渡匣). Only after du xiang are the boxes strong and durable enough.

Once the boxes are ready, they are inspected by the Imperial Kiln Factory, where an official checks the size, thickness, depth, and weight to ensure they meet the required standards. Only qualified boxes are sent to the Imperial Kiln to fire tribute porcelain.

Before making the 72-Step handmade ceramics cups, the bai dun is crushed and soaked in a large water tank. This process is called hua dun (化不).

The next day, through a washing process, the material is stirred into a slurry with wooden rakes, and coarse debris is removed by sieving and using magnets to remove iron content. After several repetitions, the slurry thickens and is left to dry and remove excess water, before being stored in a clay room for aging.

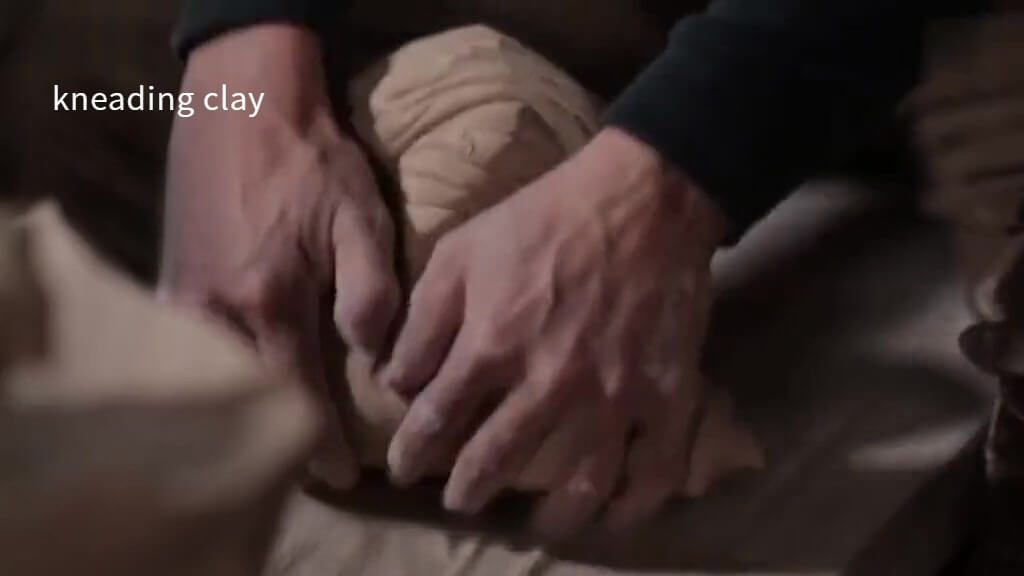

After some time, the clay is repeatedly shoveled, piled, and kneaded twice, followed by foot stamping. This refined clay is then kneaded like dough to remove air bubbles and evenly distribute moisture. This process, known as chui ni (抐泥), prepares the clay for shaping.

The well-prepared clay is placed at the center of a rotating wheel, where subtle movements of the hands adjust the clay to form the shape of the vessel. This shaping process, seemingly simple, requires decades of practice to master.

The yin bei mo (印坯模), a special mold used for shaping the inner walls of round vessels, is made from local clay. Once dried, it has a certain strength and water absorption. However, the mold may change due to the kiln temperature and moisture, so mold-making requires great skill.

After drying, the round vessel formed on the wheel is placed on a mold of the appropriate size and gently pressed into shape, ensuring that the blank’s dimensions are consistent. This process is called yin pi (印批).

To ensure the surface is smooth and even, the vessel undergoes li pi (利坯), a process where it is refined on the pottery wheel. During shaping, a clay foot of approximately 2 to 3 inches is left at the bottom of the vessel to assist in handling and decoration.

After decoration, this foot is removed, a process called gua pi (剐坯) or wa zu (挖足). Then, a base glaze is applied, and once slightly dry, the foot is trimmed.

For vessels such as cups and teapots, their handles and spouts are added in a separate process, traditionally referred to as chi shou (持手) and liu (流). Because of their shapes and placement, these are added in another step by specialized workers known as “sculptors.” These workers are not only responsible for functional ware but also for larger decorative porcelain with animal motifs and ear-shaped details.

Once the porcelain blanks are made, they must be thoroughly dried, especially in winter, as heating them too quickly can cause cracking or uneven drying. The best method is to dry them under the sun on sunny days, or during the spring and summer, they are placed on drying racks in the clay room where they are exposed to both sunlight and ventilation for balanced drying. Transporting the blanks during drying is called peng pi (捧坯).

End of Chapter 2. To be continued.